Ibrahim Lachine sold his mother’s furniture to pay for a place on a smuggler’s boat from Lebanon to Cyprus and left without saying goodbye. Stealing was, he admits, a bad thing to do, but the boat mafia wanted $700 and he couldn’t see any other way to get the money. He was 22 and hadn’t worked for three years. Food came from charities. Rent hadn’t been paid in months. Ibrahim leans back on a plastic chair, tall and angular in a black tracksuit and black running shoes. ‘We were very sad and very poor.’ Then he grins, a little embarrassed but mostly pleased with himself. He says he waited until one morning when his mother and his four sisters went out to visit a relative. He called a buyer for the furniture right away and soon the three sofas from their sitting room were being carried off. His mother and sisters returned that night to find bare walls and Ibrahim gone.

Another young, unemployed Lebanese Sunni, Mohammed Khaldoun, was also talking to the smugglers. One of his sisters sold her gold necklace to pay them. Mohammed was 27, gentle and quiet, square-jawed with a thick beard. He had left school at 10 for a workshop where he filled fire extinguishers, but he had been without a job for four years. He dreamed of starting a family, though that was impossible because he still lived with his parents and seven sisters. They all slept head to toe in one room of a crumbling building in Tripoli, Lebanon’s second largest city, in the north. His father drove a rented taxi, making about $3 a day. Mohammed thought that a laboring job in Cyprus might pay $40 a day, enough to buy his father his own taxi. His mother, a slight, dignified woman in a hijab, told me she begged him not to go. But he kissed her on both cheeks and then kissed her hands — as he did every day — and said: ‘I’m leaving.’

Both men were among 49 migrants who set off from Tripoli in September on a small fishing boat. It was perhaps 30 feet from bow to stern and everyone sat shoulder to shoulder in the open air. There were two of Mohammed’s cousins and their wives and children, a boy of three with one couple, a two-year-old boy with the other. One of the women was pregnant. The smugglers told everyone the boat might sink unless they handed over their belongings. They had to give up their bags and their food and water, even the children’s powdered milk. The smugglers demanded their phones too, promising to return them in a few hours. Ibrahim hid his in his waistband. The plan was to meet a larger vessel at an island off the Lebanese coast and then cruise to Cyprus. The little boat slipped out of harbor after midnight.

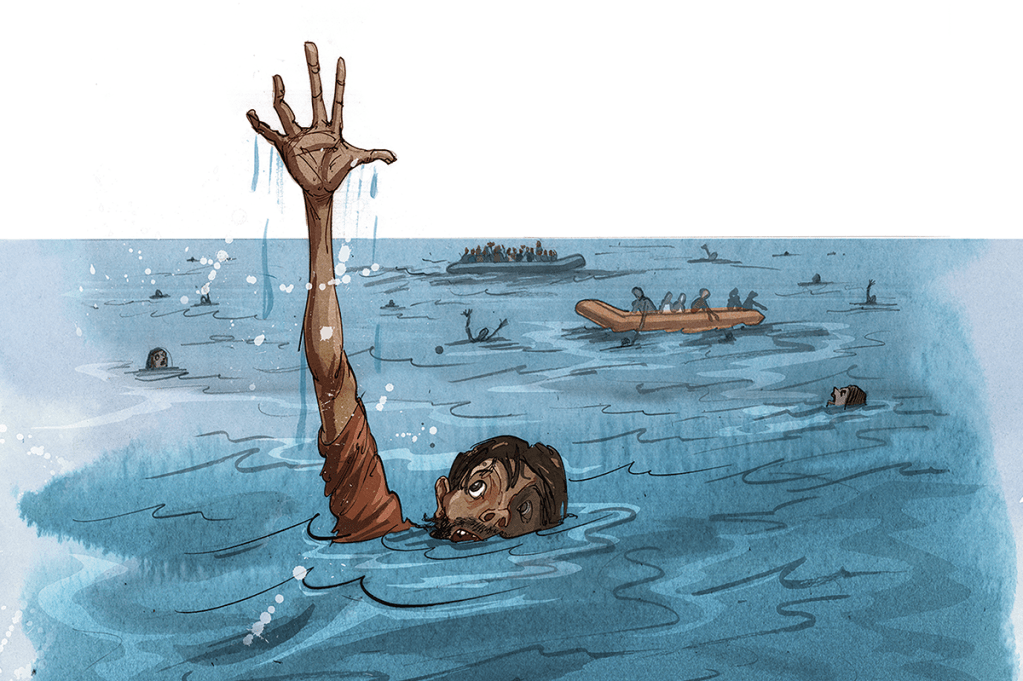

It never reached the island. Instead, it ran out of fuel and began to drift. The sun beat down and there was nothing to eat or drink. After 24 hours, the two young children were desperate with thirst and someone gave them seawater. The three-year-old died first, then the two-year-old. The boys’ fathers wrapped them for burial using strips torn from the men’s clothes. They put them in the water tied to the boat by a length of rope, hoping to preserve the bodies.

Mohammed Khaldoun felt bitter regret that he had been unable to do something to save the children. ‘I’m sorry, forgive me,’ he told their parents. ‘But I will help you now.’ He said he would swim until he found a ship to rescue everyone. ‘If I don’t come back, please take care of my mother and father.’ He took two large plastic Coke bottles that had been used to store diesel and put them under his shirt to help him float. Another man decided to join him. All anyone could see, in any direction, was water. The two men jumped in and began swimming.

After they had gone, Ibrahim remembers that the only sound was of women wailing. Two days passed and the children’s bodies began to bloat and decompose. They were cut loose and pushed away. A man died and his body was heaved over the side. Ibrahim would sometimes take the phone he had hidden and hold it up as high as he could, but there was no signal. Four more men swam for help. They, too, disappeared over the horizon. By now, everyone on the boat — including more than a dozen children — had gone seven days without food or water. Many were near death. Ibrahim agonized about what to do. He read his Qur’an, the Surah al-Haaqqa, verses about the grace awaiting the righteous in paradise. Already weak and exhausted, he knew he had no choice but to go for help too. He was the only one left who knew how to swim. Everyone was weeping, he tells me, because he was their last hope.

He wore just shorts in the water. He was stung by jellyfish and tried to push them away as he swam. He got sunburned and the saltwater made his teeth ache. During the day, he used the sun to head in the direction of Cyprus, although it was still a hundred miles away had he known it. The night was terrible. He felt — and he was — completely alone. In the darkness, he heard shudders and groans from the deep and ‘bad, hard’ voices. Why did he steal his mother’s furniture? Why hadn’t he told her he was taking the boat? She could have raised the alarm. After two days and two nights, he told me, he decided to give up and head back to where he thought the others would be. As he turned around, he saw a UN ship plowing through the water toward him. They pulled him aboard, he said, and he told them to find the boat.

Ibrahim says that everyone would have died if not for him. The UN tells a different story. A spokesman said that a peacekeeping ship had already spotted the migrants on radar and Ibrahim was found later, floating unconscious. Perhaps he is exaggerating his heroics. He was filmed recovering in hospital and said he swam for five days, not the two he told me. Yet another account has him in the water for a single day. Still, people greet him in the street and say ‘Allah protect you’. He charges for interviews and media appearances. His clothes and his phone all look new. He told me, smiling: ‘Now we have beautiful sofas.’ His mother has forgiven him, glad to have him home again.

Mohammed Khaldoun’s family knows about what he did only from the people rescued by the UN. He never came back. His mother, Afaf, told me she prayed for his return every day, though it was three months since he set out to sea. A local journalist posted on Facebook that Mohammed had been washed up in Israel and was being held there. Afaf clings to that hope. When Mohammed did not call from Cyprus as expected, the smugglers sent the family WhatsApp messages, telling them not to worry, he was fine, on a beach or being processed in a refugee camp. It was a cruel deception, one that delayed the search for several days. The family believes even worse of the smugglers, accusing them of deliberately sending everyone to their deaths so they could steal their possessions.

Most of the people on the boat that Mohammed and Ibrahim took were Syrian, not Lebanese. That’s probably true of all the migrant boats from Lebanon. Lebanese politicians tell the international community this could change: the country’s economy is collapsing; this could create a new wave of migrants heading for Europe. Such warnings are no doubt self-interested — a good negotiating tactic when asking for aid — but they are based in reality. Sectarianism, endemic corruption and a historically overvalued currency all meant the Lebanese economy could not withstand the pandemic. It didn’t help that the banks were running a literal Ponzi scheme and shut their doors when they inevitably ran out of cash. The result: a currency that has lost 95 percent of its value in a year.

A third of that decline came on a single day in March — the black-market rate for the Lebanese lira fell from 10,000 to the dollar to 15,000, against an official rate of 1,500. Protesters blocked the main highway into Beirut with burning tires; my half-hour journey home took five hours as security forces closed the road. People here worry that any trouble on the streets will eventually take on a sectarian character. My dentist, a Christian, thinks it won’t be long before the Christian militia in his neighborhood starts setting up checkpoints. He wonders, as many Lebanese do, if there will be another civil war: ‘Do you think I could get a visa to go to London?’ The rich and the well-connected are already leaving, or at least getting their money out. The central bank governor has been accused of embezzling $400m and hiding it in a Swiss bank account. He denies the allegations but, regardless, continues to print money for a government that is paralyzed and doesn’t know what else to do.

The effects can be seen on Mohammed’s family, which is now even worse off than when he left. His father can’t find fares for his taxi in Lebanon’s repeated lockdowns. A sister is the only other person in the family with a job, in Tripoli’s famous pâtisserie, Hallab. A year ago, she earned 800,000 lira a month (about $600). She’s now paid 400,000 and that is worth less than $30 after the devastating devaluations of the past year.

Down by the port in Tripoli, you can find Lebanese working for $1 a day, with no hope of anything better. Ibrahim told me that now that the weather is better, with summer on the way, he was going to take another boat. He accepted the risk of dying at sea — which he knew better than anyone — ‘because I am dying a slow death here in Lebanon anyway’. That’s something you hear often from migrants and would-be migrants in Lebanon. There will be no shortage of people to fill the next boats.

International charities are working to reduce poverty in Tripoli. You can donate to one here: www.caritas.org/donation/lebanon-appeal/. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2021 World edition.