The British government’s new white paper on immigration has been shaped by a social norm which argues that the white British ethnic majority’s interest in limiting the pace of cultural change and facilitating assimilation is racist.

The emphasis on skills rather than numbers, on economic over cultural considerations, and on rebalancing immigration away from Europe speaks to this. The document reflects the thinking of both Brexit and Remain politicians. Yet it does not align with the motives of many who voted Leave, or a considerable chunk of those who voted Remain. These voters seek lower levels of immigration, and research shows that this is driven more by identity threat than by economic considerations. If immigration numbers remain where they are after Brexit, but shift toward non-Europeans with skills, this could just as easily increase as decrease populist pressures. This is but one illustration of how the myth of white exceptionalism is fueling populism and polarization.

The notion that whites are a fallen category who can only redeem their sordid group history by denigrating or ignoring it, and that they must be judged against a different standard than other groups, is preventing a measured discussion of questions of immigration and ethnic change. This opens space for less reasonable voices who are willing to provide answers to questions many are asking.

Many liberals regard the disruptive behavior of radical anti-racist students and administrators at places like Evergreen State College, Middlebury College and U.C. Berkeley as anti-intellectual and irrational, and feel no connection to them.

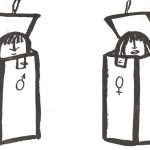

But ask yourself the following: is it racist for a white person to vote for reduced immigration? Is it racist for whites to identify with a caucasian racial image as a group symbol? Save your answers. Now let’s change the questions. Is it racist for a Chinese-American person to favor increased Chinese immigration to grow the size of their community? What about for Hawaiians to identify with a Polynesian racial image as a symbol of their group? Now recall your answers. Even if you answered these questions consistently, if you are white, you probably cringed when completing the first set.

Let’s explore this discomfort, because it explains why western mainstream elites are unable to defuse the tensions driving national populism. There is no sensible reason for answering the questions differently. Our cultural cringe can’t be a logical response based on a consistent definition of racism. Indeed, if we bracket critical race theory, which is ideologically-motivated and anti-science, there is no basis for [this response]. As political theorist Yael Tamir observes in her book, Liberal Nationalism:

‘Liberals often align themselves with national demands raised by ‘underdogs,’ be they indigenous peoples, discriminated minorities, or occupied nations, whose plight can easily evoke sympathy. But if national claims rest on theoretically sound and morally justified grounds, one cannot restrict their application: They apply equally to all nations, regardless of their power, their wealth, their history of suffering, or even the injustices they have inflicted on others in the past.’