This is a crucial year for the UK’s two most important relationships. The Anglo-American alliance, Britain’s strongest diplomatic and security partnership, now needs to adjust to a new president in the White House. Meanwhile the UK is also starting its new relationship with the EU. The question is: can the two sides move on from the wrangling of the Brexit negotiation?

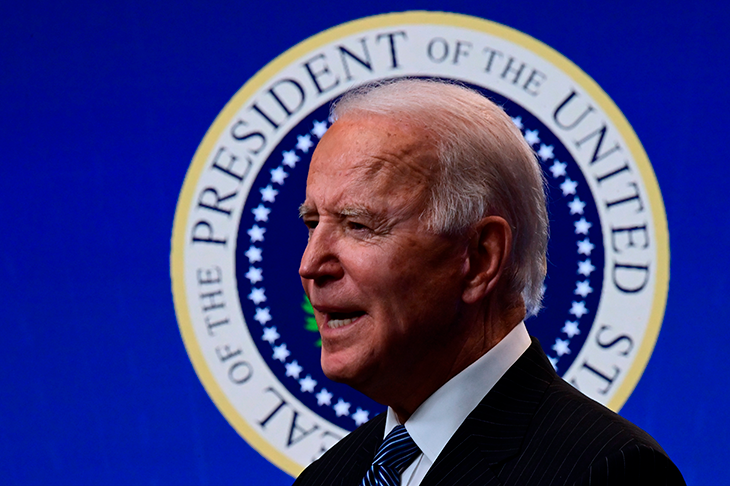

To great relief in British diplomatic circles, the new US administration and the UK have got off to a good start. Joe Biden has shown that he is keen to move on from the Donald Trump era. Small as it may seem, the fact that Boris Johnson received the new President’s first leader phone call outside of North America was a sign that Britain isn’t out in the cold, regardless of Johnson’s decision to maintain the Special Relationship during the Trump presidency. Ultimately, despite the fact Biden once dismissed Johnson as a ‘physical and emotional clone’ of Trump, the foreign policy interests of the US and the UK governments align so closely that the benefits of the alliance are obvious to both sides.

Firstly, the White House is taking a tough line on Vladimir Putin — a policy that sits far more easily in London than in Berlin, where the new leader of the CDU, Armin Laschet, has long favored a softer approach, in order to ‘avoid triggering a new confrontation’ with Russia.

There will be much talk of cooperation between Biden and the British prime minister on climate change in the run-up to the UN COP26 summit in Glasgow in November, but their work together on China will be just as significant, if not more so.

Earlier this month, Kurt Campbell — who will hold the pen on Asia policy in the Biden White House — wrote an essay in Foreign Affairs detailing ways in which the US should work with other Asian countries to check ‘Chinese adventurism’. Crucially, it highlights the importance of cooperation with India, a point also made by the new secretary of state, Antony Blinken, at his confirmation hearing. Some Democrats had been wary of working with India, given Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist tendencies. But the Biden administration appears to be taking a more pragmatic stance.

This approach simplifies things for the UK, which is keen to build on its own relationship with New Delhi. If it had not been for lockdown, Johnson would have been the guest at Republic Day this week. India is also manufacturing huge amounts of the Oxford vaccine (and donating doses of the jab to South Asian countries as part of an attempt to push back against China’s influence in the region). Johnson has invited Modi to the G7 summit this year, at which he plans to launch the D10, which brings the G7 together with India, Australia and South Korea in an alliance of democracies designed to counter China.

Campbell endorses the idea of the D10 in his essay, and also proposes two other alliances to help balance China’s rise. First, an expansion of the ‘Quad’, which organizes military cooperation between the US, Japan, Australia and India. Second, a grouping based on human rights, bringing together the 24 countries that have condemned Beijing’s treatment of the Uighur Muslims and its curtailment of Hong Kong’s freedoms. I understand that the UK would expect to join both of these alliances. This shared view on the key geopolitical issue of this decade means that the US and the UK are likely to become still more aligned over the coming years.

If the Johnson/Biden diplomatic relationship has got off to a better start than expected, the same cannot be said of the post-Brexit UK/EU one. The first month of the relationship has been defined by London’s refusal to grant the new EU ambassador the honors and privileges that Brussels feels he is entitled to; and the EU’s demand that suppliers notify the Commission before exporting vaccines to third countries such as the UK. Germany wants Brussels to go further and impose export controls on vaccines, a quite remarkable development. There are fears in Whitehall that this kind of ‘vaccine nationalism’ could aid Russian and Chinese efforts to use their own jabs to advance their interests in the developing world.

The tussle over the diplomatic status of the EU’s ambassador in London is rather absurd. The EU places great importance on having its officials treated with the respect normally accorded to nation states. The UK is insistent that he will be treated as a representative of an international organization. But if the EU actually were just another international organization, the UK would not have left it.

The whole row is a hangover from the days of membership, when the UK was understandably concerned about the EU’s pretensions to statehood, and from the tensions of the Brexit negotiations. As one government source admits, it is ‘hard to switch the switch off’. But now that Britain have left, it should perhaps indulge the EU and roll out the red carpet. As the Commission’s criticisms of the way France handled the pre-Christmas border closing showed, there will be times when the Commission is more on the UK’s wavelength than on that of member states. It is in the UK’s interests to strengthen its own direct relationship with the Commission as it works out how best to advance its interests from outside the bloc. Arguments over the status of the EU’s ambassador don’t help with that.

The severity with which the EU side has reacted to this snub is revealing. The UK has traditionally been good at flattering diplomatic egos to its own benefit; the British government should be thinking about how it can use the EU’s sensitivities to advance its national interest.

There will be plenty more rows with the EU in the next few years, as the two sides settle down into a new relationship. The EU will attempt, often in not particularly edifying ways, to assert itself as the bigger partner.

Without doubt, a significant part of the future UK-EU relationship will be competitive. The bloc will be competition for inward investment and for the custom of world markets. Ultimately, this dynamic should be mutually beneficial: it was, after all, competition between states that led to Europe’s diversity, wealth and power. But this element of the relationship should not prevent Britain and the EU from remembering that they are, foremost, allies — both with each other, and in an American-led western alliance.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.