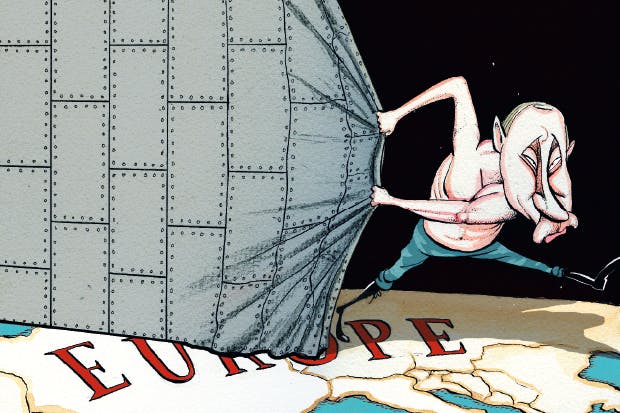

On Europe’s eastern borderlands, trouble is brewing. Two headstrong leaders — Vladimir Putin and his Ukrainian counterpart Petro Poroshenko — both with authoritarian tendencies and both facing sagging popularity at home, have swapped trading insults for exchanging bullets across the Strait of Kerch.

The frightening truth is that war would suit both presidents’ short-term interests. Poroshenko faces re-election in March, and with his ratings running at 15 percent he stands little chance of victory without a nation-uniting conflict to boost his standing. Putin, too, has seen his approval ratings sag from the 88 percent he enjoyed in the aftermath of his annexation of Crimea in 2014 to 66 percent after widespread protests over his plans to raise Russia’s pension age.

Of the two, it is Poroshenko who has most to gain from the exhilarating distraction of war. He presides over a chaotic and corrupt bureaucracy, which though less spectacularly kleptocratic than that of his predecessor Viktor Yanukovych nonetheless ranks a miserable 130th place among the 180 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. The Kiev press is full of stories of army commanders embezzling funds meant for soldiers facing off against Russian-backed separatists in Donetsk and Lugansk. Disgusted citizens have pioneered a brutal species of flash-mob where groups of vigilantes waylay corrupt officials and physically dump them in rubbish bins.

Poroshenko’s government has also been powerless to control irregular, ultra-nationalist military units such as the Azov Battalion. Partisan commanders and soldiers lounge in Kiev bars dressed in their self-designed uniforms and carrying Kalashnikovs, their jeeps parked haphazardly across the pavement in open contempt of the authority of police.

In 2015 the firebrand former president of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili was appointed governor of Odessa and attempted to clean up the fantastically corrupt bureaucrats who ran Ukraine’s biggest port. His crusade crossed powerful vested interests who ousted him in just a year — and Poroshenko was too dependent on the local bigwigs’ power to object. Last year, the International Monetary Fund even suspended vital loans after Poroshenko failed to push through reforms — such as setting up anti-corruption courts — that the Fund had insisted upon.

In a word, the high hopes of the pro-EU, anti-corruption protesters who made the 2014 Maidan revolution have been thoroughly dashed, not only because of Russia’s subsequent invasion of Crimea and Donbass but by Poroshenko’s own inability to clean up the cloaca of Ukrainian politics.

Instead, he has sought to extract financial and military support from the West by pointing to Russia’s occupation of his country — most recently by appealing to ‘Ukraine’s allies to stand united’ against Russia. On one level he is quite right, of course. The inter-national community agree that the Kremlin’s invasion was an act of aggression and a violation of international law. The presence of Russian regular troops in Donbass is well-documented by international observers. Pretty much every western leader — with the notable exception of Donald Trump — has expressed support for beleaguered Ukraine after the latest incident in Kerch.

The problem is that Ukraine isn’t doing much to help itself. The 2014 Russian invasion helped unite Ukrainians — even Russian–speaking ones — behind a genuine sense of nationhood. National day rallies in Russo-phone Kharkov and Dnipropetrovsk have attracted record turnouts, their squares filled with a sea of yellow and blue Ukrainian flags. Without Crimea or the pro-Moscow populations of the separatist Donbass, the electoral maths of Ukraine has swung unequivocally westward. But instead of implementing the pro-European, reformist hopes of Maidan, the country remains an economic basket case whose economy, media and politics are dominated by a tiny group of warring oligarchs.

Indeed, the business interests of one of Ukraine’s most politically powerful magnates, Rinat Akhmetov, may be one of the proximate causes of Russia’s recent escalation of tensions in the Azov Sea. Akhmetov, Ukraine’s richest man — and proud owner of London’s most expensive flat, a £130 million pad at One Hyde Park — owns a swath of steel mills and coal mines on both sides of the front lines in Donbass. Last year, separatists in Donetsk seized Akhmetov’s assets within their own territory. But Akhmetov has retained control of the Metinvest steel mill in the Ukrainian-controlled port of Mariupol — which depends on free passage of ships through the Strait of Kerch.

Like all Ukraine’s oligarchs, Akhmetov is also a major political player. He backs the pro-Russian Opposition Bloc, the remnant of Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of the Regions. The Kremlin has always had high hopes that Akhmetov will be able to orchestrate an electoral comeback for candidates sympathetic to Moscow — even though they have little chance of actually winning the presidency. But earlier this month Akhmetov signaled that he would not support the Kremlin’s preferred presidential candidate, Yuriy Boyko. That has split the Opposition Bloc, pitting Akhmetov against his fellow pro-Kremlin oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk — whose daughter happens to be Putin’s goddaughter.

Blocking the Straits of Kerch may be the Kremlin’s way of meting out punishment to Akhmetov for his disloyalty and forcing him to toe the Moscow line. Restarting a shooting war with Ukraine might not seem the most obvious way for the Kremlin to boost pro-Russian candidates in the elections. But many of Moscow’s actions in Ukraine have been more about sowing chaos than pursuing Russia’s long-term interests. For instance, in gaining Crimea, Russia lost any hope of there ever being another pro-Moscow government in Ukraine — a major strategic loss.

For now, Russia’s strategy seems to be to turn up the conflict a single notch, rather than launching an all-out military offensive against Mariupol. The short-term aim seems to be to damage Poroshenko’s chances in the elections by showing him to be powerless to release the Ukrainian sailors in custody in Crimea. Once the humiliation of Poroshenko is complete, the Kremlin’s calculation seems to be that the war can be further escalated or contained as political expediency dictates.

The danger is, of course, that such finely tuned military games have a habit of getting out of control. The Kremlin may have underestimated Poroshenko’s domestic support — as well as his stomach for a fight. Certainly the Ukrainian parliament’s surprise approval of imposing martial law in ten provinces that border Russia showed that he has deeper support than his poll ratings suggest. Poroshenko now has an excellent casus belli — and may yet choose to show his mettle by answering Russian gunfire with his own.

Putin has demonstrated he’s not a man to be cowed — either by western sanctions or by the defiance of smaller, weaker neighbors. He seems not to have intended the seizure of Ukrainian gunboats to kick off a full-scale war. But he may well get one, nonetheless.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.