After losing a US Senate race, Congressman George H. W. Bush was prepared to head back to the Texas oilfields and a life of relative obscurity when the new Republican president summoned him to Washington.

The president thought highly of the young man and wanted to ensure his political future. He offered Bush the Ambassadorship to the United Nations, a position that would give him a chance to remain politically relevant as he burnished his foreign policy credentials. Bush accepted.

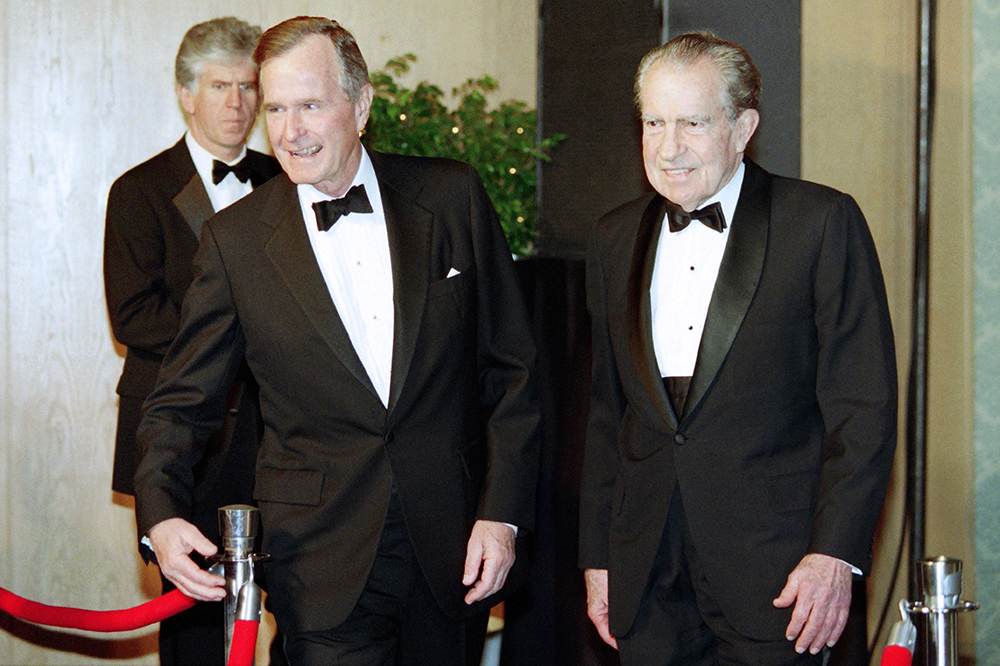

And with that, Richard Nixon launched George H.W. Bush as a national figure.

A moderate Republican with impeccable Ivy League credentials, Bush wasn’t a bull-in-a-china-shop outsider like Nixon, but Nixon saw in him a smart, ambitious loyalist who could help him negotiate the establishment swamps both here and abroad. Nixon was so convinced of Bush’s abilities that following his stint at Turtle Bay, Nixon named him chairman of the Republican National Committee at the height of Watergate. It was another position that, while thankless at the time, set Bush on a trajectory that ultimately put him in the presidency.

Nixon, perhaps the greatest foreign policy visionary to occupy the Oval Office, mentored Bush (and every president who succeeded him through Bill Clinton, except for Jimmy Carter), which helps to explain his later disappointment with Bush’s leadership at particularly pivotal moments.

Having served as Nixon’s foreign policy assistant from 1990 until his death in 1994, I had a front-row seat to much of Bush’s presidency as seen through Nixon’s eyes. While Nixon respected Bush, Nixon grew increasingly frustrated with what he considered Bush’s rather perfunctory handling of staggeringly important historical events, particularly the 1989-1990 collapse of the Soviet empire and Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

Part of Nixon’s frustration stemmed from no longer having the ability to direct epic events himself. But the majority of his irritation was rooted in having to watch those events, in his view, be mishandled. Great leadership required great vision, and Nixon grew dismayed when he believed that Bush wasn’t demonstrating either.

As I originally reported in my book Nixon in Winter, Nixon considered Bush ‘a good man, but not a strong man politically,’ who despite his extensive experience in foreign affairs, failed to respond resolutely and imaginatively to the end of the cold war. For Nixon, Bush’s foreign policy seemed to reflect dominant opinion rather than lead proactively, leaving Bush as a responder to rather than a shaper of events.

Although Nixon conceded that Bush faced a difficult challenge in formulating policy in a new and uncertain era, he faulted him for an unwillingness to take some risks in behalf of the democratic revolution then sweeping Europe.

‘The guy has to be wondering what to do,’ Nixon said to me of Bush in October 1990. ‘What does the United States do when the entire international system it has known for 45 years collapses without anything to replace it? It’s a tough nut to crack. I’m not saying it’s easy. It’s just that Bush has shown absolutely no command of this situation.’

Nixon believed that the US should pursue a principled policy that served our long-term interests. Bush’s reluctance to live up to our moral, political, social and ideological responsibility to assist the forces of democratic reform was a grave mistake, Nixon thought, and he let his frustration become known in what became known as the 1992 ‘Nixon memo’. It was a scathing indictment of Bush’s unresponsive policy toward the now-former Soviet Union, in which he proposed a comprehensive plan to shore up internal reform elements, including establishing a ‘free enterprise corps.’

The memo got the attention of Bush and his team, who began robust debate of his recommendations.

The episode was reminiscent of Nixon’s move two years earlier immediately following Saddam Hussein’s August 2, 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

As president, Nixon had ordered a top-secret intelligence analysis of Islamic fundamentalism, terrorism and expansionism, and he knew that US-led military action was likely the only way to dislodge Iraq from its neighbor. To Nixon’s relief, Bush condemned the aggression the next day, although Nixon believed he did so only because British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was present ‘to put the spine into him.’

Nixon wanted to put some spine into Bush as well, so he drafted a lengthy memorandum of military, diplomatic and political advice which he had me hand-deliver to the White House. That memo, like the later one on Russia, had its desired effect in guiding Bush’s policy thinking, and shaping, at least somewhat, the execution of the first Persian Gulf war.

As we rightfully celebrate Bush’s foreign policy record, it’s worth remembering that some of his greatest achievements were – at least in part – due to his mentor’s interventions. To his credit, Bush always listened keenly to Nixon’s counsel and carefully considered it, though he didn’t always choose to heed it in full. And while Nixon often felt compelled to prod him, he never doubted Bush’s integrity, honor or intentions.

I am certain that Bush experienced his fair share of frustrations about Nixon as well. But Bush also publicly recognized that the man who had changed the course of his life had also changed history in countless ways. Now that both men have passed from the scene, we’d do well to recognize that the country and world were – and are – better for their compelling relationship.

Monica Crowley is a contributing editor to Spectator USA and a columnist for the Washington Times.