In November, President Donald Trump repeated his call to end America’s longest war. ‘The Taliban wants to make a deal — we’ll see if they make a deal,’ he said to troops at Bagram Air Base.

And while he framed it as ‘if they do they do, and if they don’t they don’t’, the president also acknowledged the outcome ‘will not be decided on the battlefield’. Ultimately, there will ‘need to be a political solution’ that will be ‘decided by the people of the region’.

Yet when faced with opportunities to wind down the war in Afghanistan, Trump has repeatedly stopped short of decisive action. He has expressed his desire to see US soldiers come home from the protracted conflict, but deferred to the generals on the details.

Trump campaigned in 2016 against the foreign policy of his Republican predecessor, George W. Bush, defeating the 43rd president’s brother Jeb and 15 other major candidates in the GOP presidential primaries. He has consistently attacked his Democratic predecessor Barack Obama’s legacy, foreign and domestic.

Nevertheless, because of his deference to the Pentagon, Trump’s Afghanistan policy has looked in substance much the same. ‘My original instinct was to pull out, and historically I like following my instincts, but all of my life I heard that decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office,’ Trump said in 2017 when announcing an increase in troops, reminiscent of but smaller than Obama’s Afghan surge. ‘After many meetings, over many months, we held our final meeting last Friday at Camp David, with my Cabinet and generals, to complete our strategy,’ he declared in a seeming about-face from his solidarity with Americans ‘weary of war without victory’. In that same speech, Trump complained of a failed ‘foreign policy that has spent too much time, energy, money and, most importantly, lives trying to rebuild countries in our own image’.

The fiscal and human costs of the Afghan war weighed heavily on Trump long before he became president. ‘We have wasted an enormous amount of blood and treasure in Afghanistan. Their government has zero appreciation. Let’s get out!’ he tweeted in November 2013 — six years before he visited the country as Commander in Chief.

Since taking office, Trump has been slower to order a withdrawal but has continued to voice these kinds of concerns. ‘But how many more deaths? How many more lost limbs? How much longer are we going to be there?’ Trump demanded of his generals and national security advisers during one set of deliberations. According to veteran Bob Woodward’s book Fear, when hawkish Lindsey Graham objected to reported plans to reduce US military presence in Afghanistan, Vice President Mike Pence advised him, ‘You’ve got to tell [Trump] how this ends.’

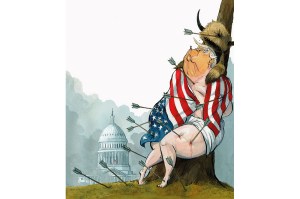

Graham, Woodward writes, replied that the war ‘never’ ends. The people Trump employs to supply him with military and diplomatic options have given much the same answer, although a drawdown of sorts is still possible before the 2020 election. Trump encountered similar resistance when he called publicly for withdrawing troops from Syria — a war Congress never even authorized as required by the US Constitution — to chaotic effect along the Turkish border. He has opposed following his hawkish Iran policy to its logical neoconservative conclusion of Washington-backed regime change. But Afghanistan has produced the most jarring disconnect between Trump’s governance and his rhetoric about ‘endless wars’: Americans have been fighting in this backwater of peripheral significance for almost 20 years.

Like many Americans, Trump has always made an important distinction between the post-9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Iraq was a war of choice that should never have been fought in the first place — or as Trump put it, ‘a big, fat mistake’. ‘We should never have been in Iraq,’ Trump said while campaigning for the Republican nomination. ‘We have destabilized the Middle East.’

Afghanistan at least began as a just and necessary act of retribution against those who shielded the planners of the 9/11 attacks. But it quickly morphed into the kind of nation-building exercise Bush promised would not be part of his ‘humble foreign policy’. That has proven much harder to accomplish — and to walk away from.

‘I’ve never said we made a mistake going into Afghanistan,’ Trump told CNN in 2015. ‘Do I love it? No. Do I love anything about it? No. I like — I think it’s important that we, number one, keep a presence there and ideally a presence of pretty much what they’re talking about, 5,000 soldiers.’ In 2017, Trump repeated this to the same network: ‘I would leave the troops there begrudgingly. I’m not happy about it, I will tell you, but I would leave the troops there begrudgingly.’

Trump’s support for the war has only grown more begrudging in the intervening years. In 2019, he nearly pursued peace talks with the Taliban at Camp David, something that would have been politically suicidal for Obama. He has continued to say the war is no longer worth the toll it is taking on troops and taxpayers. .

Among Democratic presidential candidates, Tulsi Gabbard, a veteran of the War on Terror, has emerged as the leading voice saying that Trump hasn’t gone far enough with an ‘America First’ foreign policy that would bring the troops home. Gabbard has many conservative admirers and progressive detractors. Hillary Clinton has implied the Hawaii congresswoman is a Russian asset.

But the generals have remained steadfast. So have a steady parade of Trump’s political appointees, from former defense secretary James Mattis to ousted national security adviser John Bolton — many of whom have prominently turned against the president. Trump hasn’t advanced qualified alternatives, like former Sen. James Webb, who shares his basic foreign policy views. Senate Republicans have joined in rebuking Trump for contemplating ‘precipitous’ withdrawals — a laughable adjective for describing an end to US participation in the Afghan war.

Trump is often said to be hasty, inclined to overrule the military and other experts, bullheaded and needlessly battling the ‘deep state’. On the vital matter of how long Americans remain in Afghanistan and for what purpose, that certainly doesn’t appear to be true.

W. James Antle III is editor of The American Conservative. This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition.