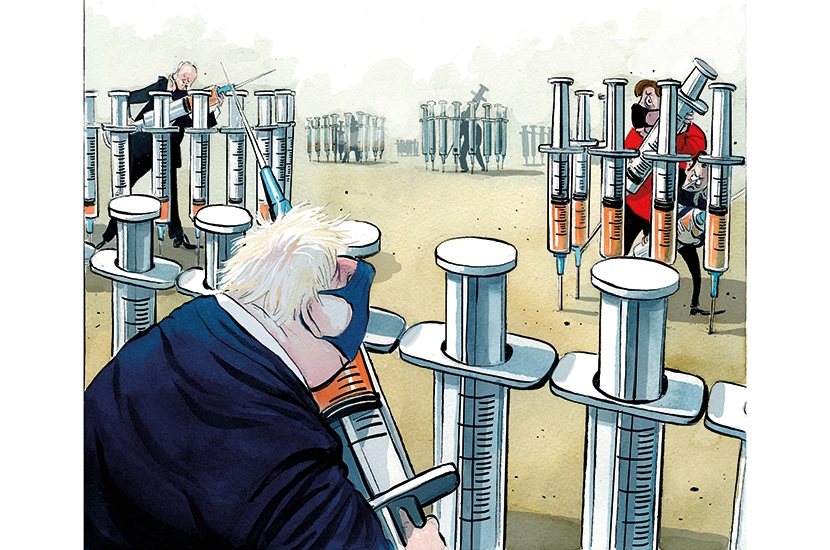

Armed guards are patrolling the perimeter fence of a sleek factory. Software experts are fending off hackers. Border officials are checking trucks and ferries, not for weapons or illegal immigrants, but for a mysterious biochemical soup, while spies and spin doctors are feeding social media with scare stories flaming one national champion or another. Welcome to the first great geopolitical battle of the 21st century. It may sound like something ripped from the pages of a dystopian sci-fi novel, but in truth we’re seeing the opening salvos in the vaccine wars.

Rather than cooperating with one another to roll out a global vaccination campaign to rid the world of COVID-19, the major powers of the world are instead descending into a fierce, increasingly nationalistic competition. The EU is threatening to hold back supplies from Britain, the Americans are scooping up supplies wherever they can, and the Russians and the Chinese are engaged in a form of ‘vial diplomacy’ reminiscent of the Cold War. It is all starting to turn very, very nasty. We are seeing how quickly our globalized world collapses when push comes to shove. The effect of all this on national security, on industrial policy and on the movement of people around the world will be felt for many years to come.

Rewind just a few weeks, and it all looked very different. First Pfizer and its German partner BioNTech, then Moderna and then Oxford-AstraZeneca unveiled one success after another. When the COVID pandemic began a year ago, lots of experts warned that it might take 10 years or more to develop an effective, safe vaccine. Nor was it ever going to be easy: keep in mind that some of the biggest drugs companies in the world — France’s Sanofi, for example, and Merck of the US, Pfizer’s great rival — failed at the first or second hurdle. To get not one but three vaccines in under one year was a miracle. As those results were revealed, it was easy to imagine that a solution to the crisis was close at hand. Except for one thing. The politics got in the way.

It turns out that deploying vaccines is harder than it looks. A quick glance at the league tables makes that clear. Israel has jabbed a remarkable 45 percent of the population, by far the highest rate in the world. The United Arab Emirates has managed 26 percent, partly with China’s Sinopharm shot. The UK has managed a very credible 10.5 percent, and the United States 6.9 percent. But the rest of Europe has been lamentable. Only 2.1 percent of Germans have been inoculated, and less than 1.6 percent of people in France — which lags behind Slovakia.

At the current rate of the rollout, it will be 2024 before most of Europe hits the 70 percent inoculation level believed to be necessary to take a population to a critical level of immunity. Australia and Japan have not even started yet, while much of the developing world is being left to fend for itself. At this rate, of the major economies, only the United States and Britain will vaccinate themselves out of lockdown this year, and both countries may have to introduce strict travel restrictions to avoid importing new strains from abroad.

Britain, spooked by the battle to find plastic gloves and other PPE in the first wave, wrote into its contract with Oxford-AstraZeneca a stipulation that vaccines made in Britain would be offered to Britain first. That was signed in May. The EU dithered for an extra three months and didn’t agree terms until the end of August. It failed to extract similar promises on delivery. It will now wish that it had.

The blame game has already started. The EU hijacked the vaccination program, wildly overpromised and then failed to deliver. It ordered too few vaccines, made some bets that went wrong (including the failed Sanofi vaccine) and didn’t put down enough money upfront to allow companies to prepare for mass production.

Like any cornered bureaucracy, and in a manner eerily reminiscent of a failed state, Brussels has lashed out, blaming everyone else. At the start of the week, the Italian prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, and the EU Council president, Charles Michel, threatened the drugs companies with legal action to ensure supplies. The saga took a darker twist when, on Tuesday, the EU said it would need to be notified before the export of any vaccines from the EU. Its commitment to internationalism seemed to have gone completely out of the window. There appears to be an underlying belief that somehow the perfidious Brits were siphoning off Pfizer and Oxford supplies that instead should have been reserved for Europe.

And yet, oddly, the Oxford shot has not even been approved in the EU: a requirement to print the label in 24 languages is reportedly one of the many hold-ups. AstraZeneca was in the surreal position of being threatened with legal action by a series of European governments for not delivering a vaccine that it is not yet even legal to sell within the EU. In an interview with Italy’s La Repubblica, AstraZeneca’s chief executive Pascal Soriot argued that because the EU had signed contracts much later than the UK, there hadn’t been nearly so much time to sort out supply issues at its plants on the Continent: ‘With the UK we have had an extra three months to fix all the glitches.’ In other words, it was the failure of the Commission to move more quickly that caused the problems, not the company.

Even more weirdly, briefings began appearing in the press — starting with Handelsblatt, the German equivalent of the Financial Times — that the Oxford vaccine might not work for the critical over-65 age group, with only 8 percent efficacy. It later turned out the German media had got itself into a muddle over the data. Only 8 percent of the people tested in the trials were between 56 and 69, but that is not the same thing as saying it is only 8 percent effective for older age groups. A mistake? Perhaps. But it is stretching credibility a little.

The German media is, as national stereotypes might have led you to expect, usually scrupulous about facts. It is hard to imagine a British tabloid making a mistake that basic even after a very long lunch. It looked suspiciously like one of the Facebook-friendly conspiracy theories Putin’s Russia might cook up. The dismal reality is that we will have to get used to those kinds of reports, even though they risk undermining faith in all vaccines. If truth is the first casualty of war, as the old saying has it, then one way of knowing you are in a war is when truth goes out of the window — and by that measure this one has already started.

There is more to the story than just the squabbles between the UK and the rest of Europe. In the background, Russia and China are using vaccines as a form of leverage. There are plenty of takers for Sputnik and Sinopharm, especially since the better-tested Oxford and Pfizer shots will be in short supply for months to come. Deals are being signed around the world, and with each one there will no doubt be strings attached. In time, President Joe Biden and his advisers will have to work out how to get vaccines out across the developing world or else surrender influence to America’s rivals for a generation or more.

Given that the two most widely used vaccines were invented in Britain and Germany, Europe should by now be leading distribution instead of squabbling over deployment. In this race, it is worth noting, the West is already losing badly. Europe has turned on itself when it should be working out how to counter the inoculation imperialism of its two greatest rivals. There will be a high price to be paid for that.

In truth, the vaccine is turning into the weapon of choice in a new version of the Great Game, an intense rivalry between competing powers, played on multiple different levels, between many different players, and with different weapons.

True, the immediate problem will fix itself to some extent. By the end of the year, we may well have a vaccine glut, with billions of doses available. There are more on the way — the Johnson & Johnson single-shot candidate is expected to report test results shortly — and production is being ramped up around the world. Making vaccines is tricky, but not that tricky; with enough money thrown at the challenge, production will get up to the four or five billion doses a year that may be needed to keep COVID at bay.

But the fierce rivalries of the past few weeks will still have long-term consequences. Countries will inevitably start working on plans for ‘vaccine security’. What will that involve? At the very least, their own research facilities, their own testing networks, probably involving ‘challenge trials’ where volunteers are deliberately infected to see if an inoculation works, and massive state-of-the-art manufacturing plants ready to crank out millions of doses in the blink of an eye.

The UK is already a long way down that track with its new Vaccines Manufacturing and Innovation Centre in Oxfordshire, designed both to perfect and manufacture new shots. But we should expect most other developed countries to match that, and probably to spend even more. In a world of vaccine wars, development and supply hubs will be as closely guarded as nuclear silos once were.

Misinformation campaigns will ripple across the internet about one formula or another, and spies will hack their way into rival national labs. At the same time, borders will close, as is starting to happen within Europe and across the Atlantic, as governments battle to keep countries free of new variants. Futurologists spent a lot of time speculating what would be the geopolitical fault lines of the 21st century. Now it seems we have the answer.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.