Sometimes a picture — the big picture — is worth more than a thousand words. Consider this Art vs Artist, Part II.

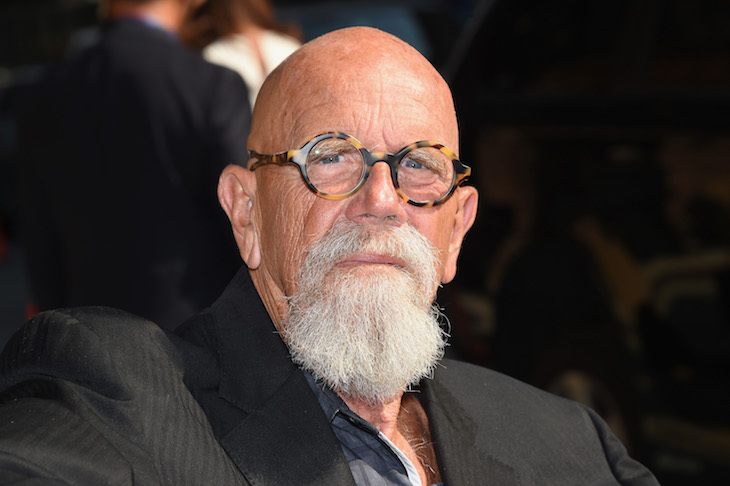

As #MeToo rolls inexorably on, the movement has scored another casualty, the wheelchair-bound, 77-year-old Chuck Close, whose reputation as a photo-realist had until last month been as immense as his paintings. Two women have come forward describing similar encounters with the artist in his Manhattan studio. Invited to pose for photographs, neither woman was forewarned that the modelling would entail nudity.

One woman confided to the Huffington Post that in 2013 she resisted Close’s request to disrobe, but then complied ‘to be polite’. Close remarked — memorably, it must be said — ‘Your pussy looks delicious.’ At which point she dressed and left in haste, declining his proffered $200; she’d made the appointment merely because she’d been flattered by the great man’s interest. In a previous instance in 2007, Close purportedly asked another young woman, then a graduate arts student, to strip, explaining only after she did so that he was working on a project photographing vaginas. Asking if he could touch her, he reached towards, but did not contact, her crotch. Alarmed, the model dressed and left, though being a penurious student, she did accept the $200. Again, no photographs were ever taken.

If these allegations are accurate (the artist disputes them), Close was clearly lewd and salacious. His motivation for scheduling these sessions appears other than professional.

Yet the larger question is whether these contested accusations justify the cancellation of a solo show of Close’s work at America’s most prestigious art museum, Washington DC’s National Gallery. Since, the New York Times has quizzed multiple galleries over whether they plan to take down Chuck Close paintings on display. LA’s Broad museum is ‘dismayed’ and ‘in active internal discussion’. DC’s National Portrait Gallery is ‘giving this news serious consideration’.

Never having touched either model, Close couldn’t be charged with sexual assault. Both women were adults, both were present by consent, and both took off their clothes voluntarily. Close’s carnal remarks were distasteful, not unlawful. He should have warned the women that they’d pose naked, but these were casual, not contractual, assignations, and he’d photographed nudes before. The encounters do sound opportunistic, disrespectful and manipulative. Chuck Close may indeed be a horny old goat, and in his studio I’d keep my coat buttoned. Nevertheless, that has nothing to do with whether his paintings are any good.

Meanwhile, Woody Allen has been subjected to a reprise of his adoptive daughter Dylan Farrow’s accusation that he molested her when she was seven. When Farrow first made the charge publicly in 1992, the accusation was exhaustively explored by the Yale-New Haven Hospital, the New York Department of Social Services and the Connecticut State Police. Multiple inconsistencies in the story led authorities to dismiss the allegation as neither plausible nor worthy of prosecution. Doubtless Dylan believes her tale. But my memories of being seven are a discombobulated hash, as if photographs from 1964 had been folded into origami and then put through a shredder. Add to this the fact that Dylan’s mother, Mia Farrow, raised her children to despise Allen for marrying her adoptive daughter Soon-Yi Previn, and the story looks dodgy times-ten.

What’s distressing about the rerun of this domestic whistleblowing is its radically more credulous reception the second time round. The holes in the story, the suggestibility and unreliability of early memory, the absence of any similar charges that Allen has assaulted other children, the mother in the background bearing a vicious grudge who is herself something of a nut — none of those factors has changed. Only the social ecology has changed, which is enough to get several headline actors to declare their regret for appearing in Allen’s films and their resolve never to act in one again. The director has been convicted of nothing. Yet Allen’s career is in the toilet. Don’t expect retrospective festival showings of Annie Hall and Manhattan any time soon.

I’ve already gone on record as resenting cultural middlemen — like the National Gallery — for coming between the arts consumer and the art because the artist has been deemed unsavoury as a person, as if we need to be protected from bad influences. I want to decide for myself whether that creepy remark about genitals turns me off attending a Chuck Close exhibit. Besides, what’s better, a washer that leaks made by a mensch, or a washer that works made by a lout? Same logic: I’d rather watch a great movie whose actors are wasters than a terrible movie with a cast of paragons.

But let’s take a step further back.

Long ago in this #MeToo mêlée we stopped making any distinction between behaviour that is criminal and behaviour that is merely obnoxious, boorish, misguided or pathetic. If we require artists to adhere to a more exalted etiquette than the one prescribed by law, why anoint sexual misconduct as more egregious than any other kind?

To an extent, this is an employment issue — and we do, effectively, employ filmmakers and painters to entertain us. What are the rules of fair dismissal? If displaying poor taste or social cluelessness (see: Aziz Ansari) are sufficient to get you sacked, I see no reason to privilege a failure to clear a high moral bar of a sexual nature above all other short-of-illegal behaviour that’s still a little disappointing. Perhaps we should banish the work of artists who engage in — not evasion — but tax avoidance. Who don’t donate to charity. Who forget to feed their cats. Who don’t recycle.

Are we employing these folks to do a job, or are we employing them to be nice people? Ironically, in this atmosphere of consuming rectitude, the much discredited ‘morality clause’ is returning to Hollywood contracts — a clause used in the 1940s to control female stars, who were sometimes forced to get abortions because their sexual reputations were regarded as studio property. I wonder if we’re not in danger of subjecting men to the same servitude.