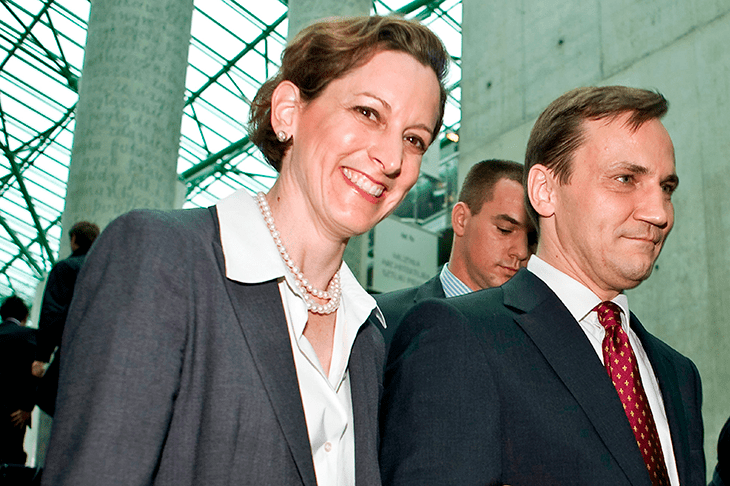

A book about breaking confidences, not to mention friendships, rather begs the same in return. Reading Anne Applebaum’s brief memoir of the world going mad around her sparked a memory of my own. It is a couple of days after the Brexit vote, and several hundred of us have gathered in London for the memorial service of a recently departed friend. The ceremony was hardly over before Applebaum and her husband, the former Polish defense minister Radek Sikorski, started picking political fights with the other guests, including some very old friends. ‘Don’t go near Anne and Radek,’ one mutual friend said to me, signaling to the visibly furious couple: ‘They’re absolutely spitting.’

There is a tradition of books by intellectuals recounting their fallouts with their former friends. Applebaum, a former deputy editor of this magazine and justly celebrated historian, frames her memoir with two actual parties: one at her restored mansion in Poland on the eve of the millennium, the second at the same house in the summer of 2019. In the years between she has parted ways with many of the guests at the first celebration. All had been elated by the events of 1989 and hopeful about the post-communist future. Twilight of Democracy is her attempt to explain that divergence of ways. Perhaps predictably, she finds other people to be most at fault.

The book begins with Applebaum’s fallouts in her husband’s native country, as the Polish public rejected his political party and voted in a rival. She then does a whistlestop tour of Hungary and what she believes has gone wrong there. After this we travel to Britain and the Brexit vote, where the ‘Vote Leave campaign proved it was possible to lie, repeatedly, and to get away with it’. Next Spain, where the Vox party is both not in government and not to her taste. Finally we are in America, where the election of Donald Trump provides the crowning horror of a strand of politics which she has by now made clear she abhors.

This is already very over-trodden ground. What makes it new is only what Applebaum is willing to spill about her former friends. Generally these are journalists or former journalists. They include one who was a friend of her husband’s at Oxford and is now our prime minister. Though Boris Johnson only ever appears to have been kind to her, Applebaum claims that over a private dinner in 2014 he said: ‘Nobody serious wants to leave the EU.’ This is the most significant betrayal of confidence in the book, but the whole thing is littered with quotes of what friends said in private years ago. One wonders if a similar betrayal of the Applebaum-Sikorski table-talk would be less or more shocking than anything described here.

All this is used to bolster the explanation of what Applebaum believes has gone wrong on the political right. Her former friends are accused of power-hunger, cynicism, love of money and much more. We are told that the public, from Eastern Europe to America, has been misled into voting for the wrong people.

Perhaps I may posit a contrary interpretation of events. While some people viewed 1989 simply as the beginning of the opportunity for representative democracy, others saw it as the chance for a permanent political class to rotate the offices of state among themselves. The Sikorskis had the position, the contacts and even the mansion. Then things started to go wrong.

In 2014, while Radek was still a minister, tapes of his conversations were leaked, their undiplomatic contents making embarrassing headlines around the world. The Sikorskis were right to feel bitter that, while the press enjoyed the scandal, almost nobody bothered to ask who might have recorded the conversations, and which foreign state’s interests might have been served by leaking them. Such things could turn anyone sour. But as Sikorski’s party was ejected from power, the sourness turned into a worldview. And as publics across the democracies asserted similar rights to upset the system, a certain type of person developed all the bitterness and fury that can come from membership of an upended political class.

[special_offer]

Why pretend that votes such as the Brexit one were gerrymandered by shadowy bots? Why not contend with the sincere arguments of sincere people, not to mention public majorities? It is not quite good enough to say occasionally that the EU has its faults and then assert that the British public were just tricked into voting to leave it. Or to spend years calling for member states to fulfill their Nato commitments and then criticize President Trump as anti-Nato when he demands the same.

Good memoir-writing should not just be critical: it should be self-critical. And the problem with suggesting that various governments around the world have dishonestly manipulated their way into power is two-fold. Obviously it wrongs to varying degrees the people so caricatured. But the larger intellectual problem is that it deprives Applebaum, and others, of the opportunity to reflect on what, in their own political outlook, might have gone wrong.

Rather than being the end of democracy, perhaps the current era is just some sort of corrective, that will itself be corrected in due course. Applebaum should plan another party for 2040, with the hope that by then she and her former friends will have learned to speak amicably again.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.