Red Dog

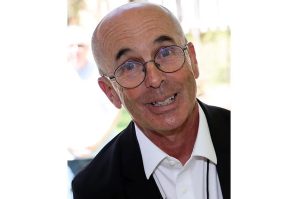

is an ambitious hybrid of a book. It was published in South Africa to wide acclaim in 2014 and has been expertly translated by Michiel Heyns, who has retained the cadence and some of the vocabulary of the original Afrikaans — the mongrel tongue that evolved in the Dutch East India Company’s Cape colony.

Willem Anker brings South Africa’s bloody birth to life through the story of Coenraad de Buys. The priapic founding father of a nation of bastards, he is a pillager and survivor, a rapist and husband, a colonist and outlaw, a rebel and hero. With his numerous wives and children, he is the gargantuan progenitor at the centre of this sprawling tale, pushing those with whom his life intersects — his intimates and his enemies — to the periphery.

The novel is set on the porous borders of the Cape colony at the cusp of the 18th and 19th centuries. This period, in which Europe was convulsed by revolutionary change, saw the rapid switching of colonial powers — Dutch, French and English — at the Cape, and Anker describes the dark twinning of freedom and power that lies at the heart of modernity and the colonial project:

‘News from Europe is slow coming to the Cape… but seditious ideas from France make landfall here faster than any new dress patterns. The words liberté, égalité and fraternité are insubstantial and vague enough to fly over at speed. In Paris, the citizens storm the Bastille in the name of liberty, and on the eastern frontier there’s nothing left but liberty. Indeed, as is always the case with messages that have to travel too far, the French slogans have a totally different look when they arrive, scurvy-ridden and scuffed, in Graaf Rijnet.’

Red Dog

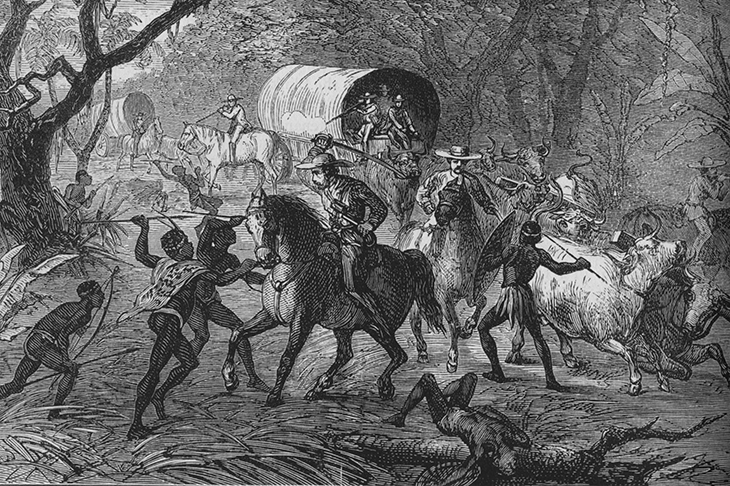

is part novel and part historical account. Anker draws skillfully on the Cape’s patchily written archives, finding traces of Buys in various travelers’ accounts and warrants for arrest, and records his duplicitous work as an interpreter between the Xhosa on one side of the Fish River — the colonial border at the time — and the white settlers on the other. Like all colonial histories, this one is inked in blood. Anker spares no detail in describing a brutal frontier society, in which slavery was legal and the genocide of southern Africa’s original inhabitants, the Bushmen, was sanctioned. Buys participates enthusiastically in many murderous sorties.

Gaps in the official record are filled by Buys’s vividly evoked interior life, and an omniscient narrator who draws the reader to him. ‘Zoom up into the heavens with Omni-Buys,’ he instructs, ‘and survey the Great Fish from above.’ This panoramic view allows for sweeps of land and time: it is the eye of history.

Red Dog is also a contemporary reckoning with South Africa’s post-colonial present, as the country grapples with conflicting origin stories, claims of ownership of the land, and violence. The Omni-Buys asks the reader:

‘Do you also smirk when you read how the terrorists of one authority are accorded amnesty and declared freedom fighters by the next succession of wigheads? Do you also want to cry out: The past is not dead, it’s not even past?’

The country that Buys inhabited was one in which there were almost no limits on the violence that was meted out by those who had the firepower to control anyone who stood in the way. It is a savagely Hobbesian world in which life, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short, was devoid of any of Rousseau’s imagined nobility — a place that J.M. Coetzee explored in his first novel, Dusklands. This reprise of the murderous origins of colonial dominion over South Africa is timely — and depressing, in that the violence of the past continues to blight the present.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.