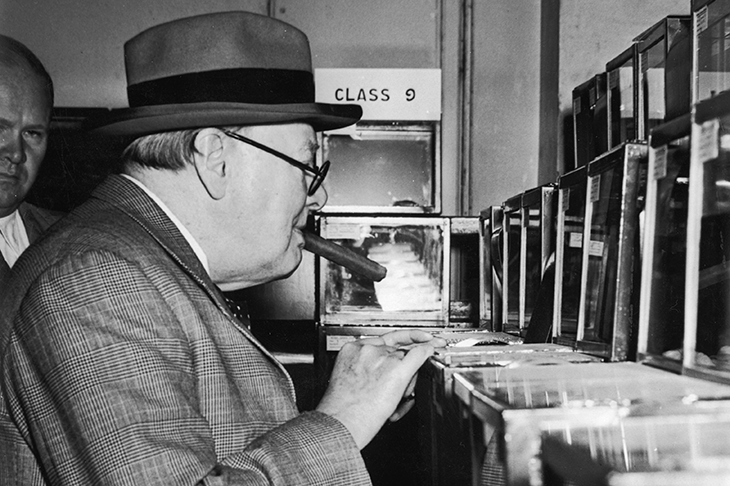

Churchill was the first British prime minister to appoint a scientific adviser, as early as the 1940s. He had regular meetings with scientists such as Bernard Lovell, the father of radioastronomy, and loved talking with them. He promoted, with public funds research, telescopes and the laboratories where some of the most significant developments of the postwar period first came to light, from molecular genetics to crystallography using X-rays. During the war itself, the decisive British support for research, encouraged by him, led to the development of radar and cryptography, and played a crucial role in the success of military operations.

Churchill himself had a scientific grounding that was hardly extensive but was nevertheless sound. As a young man he had read Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and studied an introduction to physics: the essential things, we might say. He followed scientific advances with considerable interest, to the extent that in the 1920s and 1930s he wrote articles on popular science. For good or ill, he was the person who signed the fateful note sent to the father of quantum mechanics, Niels Bohr, in Copenhagen, inviting him to flee Nazi-occupied Denmark to join the Allies and to initiate the atomic program.

In Nature magazine, the American astrophysicist and author Mario Livio describes an unpublished text from 1939, revised in the 1950s, in which Churchill discusses a scientific issue of great relevance today: the possibility that life may exist elsewhere in the universe, on planets similar to Earth. Churchill’s analysis is surprisingly lucid, demonstrating an uncommon capacity for scientific language. Anticipating the conclusions that would be reached within the scientific community in the coming decades, Churchill identified the elements that would enable forms of life similar to those on Earth to develop elsewhere: planets with the required distance from their mother star, which allowed them to maintain temperatures within the small bandwidth in which water is liquid, and with a large enough mass to sustain a sufficiently dense atmosphere.

Then there is one particularly impressive passage: Churchill notes that the most credible contemporary theory on the formation of planetary systems — the close encounter of two stars — makes the conditions required highly improbable, and hence life rare; but he notes further that this conclusion depends on the validity of the theory regarding close encounters, and no one can say for sure whether the theory is correct. Not only was this great statesman capable of valuing the importance of the scientific knowledge that he encountered, but he also had an acute sense of its margin of uncertainty. The theory of close encounter or close passage did in fact turn out to be mistaken, and today we know that planets form in a different way, from the aggregation of much smaller fragments. Churchill’s main conclusion is close to the one that we hold today.

***

Get a print and digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $7.99 a month

***

With thousands of millions of nebulae (galaxies), each one containing hundreds of millions of suns, the probability that there is an immense number containing planets where life is possible is high. The comment that follows captures perfectly, for me, something of the English spirit:

‘As for me, I am not so terribly impressed by the successes of our civilization as to believe that in this immense universe we represent the only corner where there are living and thinking beings, or that we may be the highest level of mental or physical development that has been reached in this vast expanse of space and time.’

Churchill clearly saw the limits of science. ‘We need scientists in the world,’ he writes in 1958, ‘but not a world for scientists.’ And he adds: ‘If, with all the resources that science has put at our disposal, we are still unable to defeat hunger in the world, we are all culpable.’ But he was profoundly aware of the central role of scientific thought for humanity; of the importance of politically supporting it, of listening to it, and of using it. Above all, he was aware of the great advantage it offered in allowing him to come to political decisions based on the facts — the simple secret that has contributed significantly to British and then American political supremacy in the last two centuries. Churchill knew how to think with the clarity of scientific intelligence.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.